Global Health Blog

Students for Global Health is a student led network dedicated to advocacy and action for global health equity, it provides peer to peer training through more than 30 branches and affiliates across the UK and participates in European and international meetings as a member of IFMSA the International Federation of Medical Student Associations. As Interim Chair of the Board of Trustees for this charity I provide some blog posts and other materials. Students for Global Health website is here I would urge all students who care about these issues to join.

bm

I have tried to respond to ongoing challenges to global health equity and include a stop press item in many cases as events and news hit the headlines, these are ongoing issues.

How Can Medsin Respond to the Global Gag Rule?

The Global Gag Rule, which withholds US health AID from any organisation making any sort of reference to or advice on abortion, will have a devastating effect on the lives and health of millions of people, as explained in the recent Guardian article here. This rule has been applied by Republican Administrations since it was first introduced by Ronald Regan in 1984. This time the restriction has been applied not only to $595m for Family Planning Services but all $9.5 billion US health Aid. This means any health service making mention of safe abortion services may expect a sudden funding cut. This will disrupt the provision of family planning services, condom provision, HIV/AIDs services, health support for LGBT+ people and many other basic health services. As a consequence it is likely to increase unplanned pregnancy and unsafe abortion rates.

The reason for the Gag Rule lies in US domestic politics, the “Roe vs Wade” ruling by the US Supreme Court in 1973, that legalised access to safe abortion services is still contentious. Abortion has come back into the news with the death last week of the original “Jane Roe” – Norma McCorvey, who argued on both sides of this issue following her religious conversion. Currently Gallup Polls suggest only 19% of Americans believe abortion should be illegal in all circumstances in the US, 50% say it should be legal in some circumstances and 29% say it should be legal in all circumstances. However, those opposed to all abortion are a powerful minority within the Republican Party.

In response the Netherlands Government is currently leading a coalition of more than 20 countries to establish a safe abortion fund to plug the estimated $600 million gap in aid funding and to send a message of support for countries and agencies that need this support. They are seeking the widest possible support for this initiative. Perhaps a Medsin Member would like to start a movement to get students to sign up and support this initiative. Though the amount of money that students could be expected to raise will naturally be limited, the act of providing a donation, however small, and signing an online petition would show solidarity with the millions of women and people of all genders who will suffer as a result of the Global Gag.

My experience of working with the IPPF and health services and communities in Africa and Asia suggests that even a small donation can make a difference and messages of support and solidarity really are felt even in remote communities. Abortion is not an easy option in any community and the circumstances that lead to such difficult decisions must be stressed. Those Medsin Members who have seen the world through electives or travel will know this.

Adolescent Health and Confidence in Who We Are

The WHO report "Health for the World’s Adolescents" published in 2014 highlights the fact that worldwide, for those between 10 and 19, depression is the predominant cause of illness and disability and suicide is one of the top three causes of deaths. For those countries where survey data were available, 5% to 15% of younger adolescents (ages 13–15) reported a suicide attempt in the 12 months before the survey. Adolescence is a period of exploration and discovery when we develop our understanding of and hopefully confidence in, our sexuality, body image and our relationships. The Medsin affiliate, Sexpression: UK here empowers young people to make decisions about sex and relationships by engaging students in running informal but comprehensive sex and relationship education sessions for adolescents in the community. In this brief note I explore some questions that Medsin may wish to address in respect of youth health and confidence in the UK and globally.

In the UK the Office for National Statistics report that in 2015, 3.3% of people aged 16 to 24, identifying themselves as LGB, the largest percentage within any age group. This survey seems to assume that sexuality is binary, which it clearly is not. Even in the Kinsey Report of 1948 sexuality was measured on a six-point spectrum. A 2015 YouGov poll found 49% of young people between the ages of 18 and 24 defined themselves as something other than completely heterosexual. Moreover, this does not answer the question “How many young people worry about their sexuality?” to which I would be surprised if the answer were not “All of us”.

In some countries anxiety about sexual identity is reinforced by national laws, 84 countries still outlaw homosexuality. The UN Human Rights Commission (UNHRC) recognised LGBT rights in 2011 and the following year published a report documenting violations of these rights, urging all countries to enact laws that would protect them. In 2016 the UNHRC passed a resolution to appoint an "independent expert" to find the causes of violence and discrimination against people due to their gender identity and sexual orientation, and discuss with governments about how to protect those people. The milestone resolution has been seen as the UN's "most overt expression of gay rights as human rights”.

WHO still faces obstacles in addressing this issue, until 1992 it classified homosexuality as a “mental illness". As recently as 2013, Egypt blocked a WHO discussion on LGBT health. And there are ongoing discussions on the classification of transgender sexual identity (see the article in the current WHO Bulleting here) It therefore remains important for Medsin to raise LGBTQI health rights as an crucial aspect of Youth and Global Health through the IFMSA at WHA. The WHO 2014 report called for an approach to adolescent health, including a social response that engages and listens to their concerns about sexuality and the many other different aspects of identity.

Thus for example, body image anxiety inflamed by distorting media focus and advertising that promotes unrealistic stereotypes is also a global issue affecting adolescent health. Anxiety about body image can have a seriously negative impact on health, leading to depression, suicide, anorexia and bulimia. The UK All Party Parliamentary Group on Body Image in 2012 found: half of all girls questioned and one quarter of boys believe their peers have body image problems, 60% of girls and 20% of boys have been on a diet to try to lose weight by the age of 16. By their early 20s: 12% of girls and 8% of boys have used diet pills, 8% of girls and 1% of boys have made themselves vomit, and 5% of girls and 2% of boys have used laxatives to lose weight. Another example relates to racial and religious identity, awareness of which develops during adolescence. Without support, racial and religious stereotyping can be confusing and even lead to isolation and extremism. People with physical and mental disabilities struggle to come to terms with their identity, as I saw as the Chair of Trustees of a charity that provided a school for children with special needs. But I also saw the joy of these youngsters when they overcame their obstacles.

Each of these dimensions of identity development can be the focus of bullying at schools. Stonewall estimated in 2012 that two thirds of lesbian, gay and bisexual young people reported experiencing homophobic bullying at school. Beat (Beating eating disorders) conducted a survey of 600 young people in the UK and found that at least 90 percent of respondents admit to being bullied at some time in their lives, and more than 75 percent of individuals suffering from an eating disorder state that bullying is a significant cause of their disorder. A survey by Mencap found that 80% of children with learning disabilities have been bullied. There are also reports of a rise in anti-Muslim, anti-Sikh, anti-Jewish and racial bullying in the last year sometimes linked to anti-immigrant sentiment stirred by the Brexit vote. Bullying is not only a significant cause of mental anguish, it is also a portent of social discrimination and bias at work and in our communities.

Medsin and its partner Sexpression: UK remind us that support for adolescent health issues at national and international levels can engage young people at local levels in taking action to resolve their own mental and physical health concerns. They create a supportive culture that empowers young people to become masters of their own identity and health. The forthcoming Medsin Global Health Conference, “Gender and Health: Seeing the Spectrum” on the 25-26 February at UCL London will be an opportunity to explore these issues.

Stop Press

Last year I saw the film "Moonlight" which deals beautifully with many of these issues of adolescent and young adult sexual, racial and stereotypical identity. It is a tough view but worth it. This year I read Grayson Perry's book "The Descent of Man" which is a fascinating discussion of how we need to rethink what it is to be a man, I would recommend this to anyone thinking through these issues.

Developing, Emerging or Low Income and the 99%

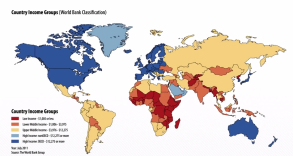

Map of low, lower-middle, upper middle and high-income countries

In the 2016 edition of its World Development Indicators here, the World Bank decided to stop using the terms “developing” and “developed” to describe countries. This is because there is no clear definition of such terms, they seem to imply that all nations will chose a similar path to “emerge” from traditional society to an industrial economy and that “developed” countries are superior because they are richer. While there have been various attempts to introduce a “Human Development Index” see here, it is notable that the most “developed” nations included a country which does not allow women basic rights, and one which sees the deaths of thousands of people each year because it cannot agree gun controls.

The World Bank 2017 Indicator Tool can be used to show: population, health and poverty by income levels based on annual GNI (Gross National Income) per capita, at average exchange rates (Atlas method) in US dollars, and poverty levels based on $1.9 per day (at PPP) in 2012. This analysis can be extended to show a variety of health related outcomes by income level or by country, for example:

- Low income countries $1,045 or less, 0.64 billion people, of whom 46.2% live in Absolute Poverty, Life Expectancy at Birth 60.2 years, Deaths from Communicable diseases 58.2%, Deaths from NCDs 31.6%, Access to Improved Water 63.5%, Access to Improved Sanitation 27%, Total Health Expenditure per Capita $85.5, Out of Pocket Spend as % Health 38.3%, Physicians (per 1000) 0.1.

- Lower middle income $1,046 -$4125, 3 billion people 16.4% living in Absolute Poverty, Life Expectancy at Birth 66.7 year, Deaths from Communicable diseases 32.5%, Deaths from NCDs 56.7%, Access to Improved Water 87.1%, Access to Improved Sanitation 49.8%, Total Health Expenditure per Capita $233.5, Out of Pocket Spend as % Health 55.5%, Physicians (per 1000) 0.8.

- Upper middle income $4,126-$12,735, 2.6 billion people 2.7% living in Absolute Poverty, Life Expectancy at Birth 74 years, Deaths from Communicable diseases 9.9%, Deaths from NCDs 81.4%, Access to Improved Water 93.6%, Access to Improved Sanitation 77.8%, Total Health Expenditure per Capita $813.5, Out of Pocket Spend as % Health 32.8%, Physicians (per 1000) 2.

- High Income $12,736 or more, 1.2 billion people 0.4% living in Absolute Poverty, Life Expectancy at Birth 80.2 years, Deaths from Communicable diseases 6.5%, Deaths from NCDs 87.5%, Access to Improved Water 99.4%, Access to Improved Sanitation 99.3%, Total Health Expenditure per Capita $4,899.6, Out of Pocket Spend as % Health 13.7%, Physicians (per 1000) 2.9.

At global level the overall trend show a decline in the numbers of people in Absolute Poverty by about 35-45 million per year. This might suggest that poverty could be eliminated in about 20 years. While there has been slow progress in reducing absolute poverty, the report from Oxfam published at the WEF Davos meeting last week (16th January 2017) “An Economy for the 99%” showed rapidly rising inequality in 7 out of 10 countries. The report on this issue can be accessed here . It shows that the 8 richest men own as much wealth as the 3.6 billion poorest people on the planet. And the world’s 10 biggest corporations together have revenue greater than that of the government revenue of 180 countries combined.

Discuss how can you advocate for equity in health

<< New image with text >>

Corruption in Health and its lessons for Medsin

Corruption arises in many different forms and situations in both rich and poor countries and health is no exception. It is a major obstacle to development as it breaks down trust between the people and government at all levels and it penalises the poor and powerless. Low income countries are estimated to lose more than a 1$ trillion per year to corruption. While it might be argued that corruption is a national issue rather than a global concern, tax laws and havens, lack of regulation and sometimes lax control of aid monies all contribute to the problems.

Transparency International is a movement dedicated to fighting corruption with chapters in 100 countries including the UK. In some respects it is a little like IFMSA and Medsin. You can visit their web site here . As it says “From villages in rural India to the corridors of power in Brussels, Transparency International gives voice to the victims and witnesses of corruption. We work together with governments, businesses and citizens to stop the abuse of power, bribery and secret deals”. On January 25th TI launch their annual Corruption Perceptions Index which calibrates levels of corruption as shown in above map where deep red indicates most perceived corruption.

The scale of corruption varies from petty demands for cash by police or other officials (including public health inspectors, doctors and nurses) to "grand scale", which can include presidential or ministry level profiteering from trade and aid. In many countries corruption can be described as “systemic” meaning that it is seen as “the way the system works”. This was certainly true for health systems in some of the countries in which I have worked.

Corruption can be fuelled by global corporations such as BAE and Rolls Royce, who offer bribes through third parties. Manipulation of trade and interfirm accounts to hide profits in tax havens is morally corrupt but legal due to the weakness of global governance. A discussion of global corruption can be found at the Global Issues page here.

In 2016 TI produced a report on “Diagnosing Corruption in Healthcare” here. This identified 8 areas of healthcare and pharmaceuticals vulnerable to corruption:

- Health system governance

- Health system regulation

- Research and development

- Marketing

- Procurement

- Product distribution and storage

- Financial and workforce management

- Delivery of healthcare services

Working in East Africa, Asia and Europe I have seen examples of corrupt practices at all levels. I have faced a president demanding a multi-million dollar aid project in his home town, government agencies diverting aid funding for clean water provision for personal housing and the corrupt management of hospitals and health supplies. I have seen examples of doctors who leave their jacket on the chair at the public hospital where they are supposed to work while away dealing with their private patients. Doctors and nurses demanding money from patients and prescription drugs issued to “patients” who simply sold them on. It is important to note that corruption is not confined to low income countries, it is a global threat. Sometimes elements of corruption are seen as cultural. In Greece “gratitude payments” are offered to doctors in envelopes of crisp new banknotes. In East Africa less pristine gifts may be requested in a more direct way.

These "informal" payments to medical staff and for medicines plus the cost of travelling to recieve care explain the high cost of healthcare to patients in low and middle income countries.

Many Medicine members may find some evidence of corruption while undertaking an exchange or elective. My advice would be to handle the situation with care. Gather evidence and report what you find to the National Exchange Officer and perhaps contact TI through them but be aware it is important to understand the full context of the situation and you may be dealing with a very sensitive situation. At organizational level I would encourage Medsin to develop links with Transparency international and to see the fight against corruption as an issue of global equity in health and development.

Stop Press

Since posting TI have published their 2016 report which highlights links between inequity and corruption.

Join the Discussion at the Global Health Centre Geneva

The Global Health Centre of the Graduate Institute Geneva, is recognized by the WHO as a leading research centre on global health governance and a centre of excellence in global health diplomacy worldwide. It is led by Professor Ilonal Kickbusch who has worked with the WHO at senior levels and was Professor of Global Health at Yale University and directed by Michaela Told who brings experience of working with the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement at local, regional and international levels. Medsin may claim a link to the Centre through the BoT as both Stephen Matlin and I, Graham Lister are Senior Fellows.

The Global Health Centre see here provides events and discussions on aspects of global health governance and diplomacy through meetings in its Geneva lecture theatres and online. It also runs courses for executives and students in Geneva and throughout the world. These courses have included a ten-week online training and development programme for WHO Heads of Country Office which I helped to develop and tutor and a special programme for IFMSA participants at World Health Assemblies which Michaela and I have supported see here. The Centre also has an active research programme into aspects of global health governance and diplomacy focused on current issues and concerns. It publishes a wide variety of research reports, policy papers, think pieces and books.

I would encourage Medsin members to sign up to their mailing list, to join in online GHC events or participate in Geneva meetings as well as receiving newsletters and updates from the Graduate Institute.

Stop Press

On the 6 March the Global Health Centre will host a meeting with the contenders for the post of WHO Director General. This is an opportunity for Medsin members to join a podcast to see and hear the new leaders. You may even be able to submit a question.

How can Medsin support better Access to Medicines?

Medsin members will be aware that access to medicines is crucial to global health equity. Currently access to vital medicines is limited for people with low incomes by three key factors. First medicines are often unaffordable because prices are set by rich country markets and may even be higher in low income countries. Second the prospect of low affordability deters the development of medicines for neglected tropical diseases resulting in what is known as the 10/90 gap. This means that only 10% of research funding is devoted to conditions that cause 90% of the global disease burden. Third the lack of effective health systems including diagnostic and prescribing skills and logistics for the delivery and control of medicines inhibits the provision of medicines as one aspect of effective healthcare. This blog considers what Medsin members can do to address these issues in the light of the UN Secretary General's High Level Panel Report on Access to Medicines, which will be debated at this year's World Health Assembly, here.

The global social contract with pharmaceutical companies embodied in WTO intellectual property agreement (TRIPS), provides global protection for 20 years for patented drugs. While patent protection starts from the filing of the patent application, which can be several years before commercial availability, pharma companies can extend this by introducing minor enhancements to their drugs. The Doha declaration of 2001 provides exception in the case of health crises, allowing the provision of lower cost generic medicines, of which India is the largest producer. Some companies provide medicines at a lower price to low income countries through intermediaries such as the Clinton Foundation. It has been suggested that the main obstacle to setting affordable prices for low income countries (where prices are often higher) is the fear of so called parallel exporting (corruptly selling drugs back to high income markets) and counterfeit medicines (an estimated market of over $75 billion).

More than one billion people suffering from one or more neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) benefited from large-scale treatment programmes of preventive chemotherapy in 2014 as part of perhaps the world's largest public health intervention led by the WHO. This programme benefited from donations of drugs from pharmaceutical companies worth billions of dollars. It also identified the need for the development of affordable diagnostics, drugs and insecticides targeted at NTDs. It is perhaps unsurprising that this programme has remained largely unknown in the western press because these diseases are not thought of as threats to health in high income countries. Medsin members may wish to see the paper here The WHO convenes a panel of scientists and health experts every year to identify the diseases they consider most likely to cause the next global health emergency. This year the list is headed by three relatively little-known NTDs: MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, known as Camel Flu), Lassa fever and Nipah virus.

The greatest obstacles to the delivery of medicines in low income countries, noted by the WHO, are the level of insecurity and the weakness of health systems. The problems vary from country to country, but the underlying issue is a lack of funding. My experience in East Africa was that in rural areas, where more than 70% of people live, health services were led by nurses and midwives with support from a medical assistant with two years training to prescribe a limited range of essential medicines, usually dispensed from tins. The situation is improving as “E-health” services are introduced but this is limited by the training of local staff in using such facilities. If the need for a medicine is identified (other than the locally available essential medicines) patients must travel to a pharmacy (formal or informal) to buy what they can afford. This often means that they do not complete a course of medicine, which leads to antimicrobial resistance. The service is likely to be very expensive for patients who bear 30- 60% of the cost (government health services provide 15-30% with a similar level from aid or charitable sector provision).

The key question is what can be done to improve access to medicines for those with greatest need and how can Medsin members advocate for and take action to improve the situation? One step is of course to press for government funding including renewal and extension of its support for the Neglected Tropical Diseases Programme. Medsin branches might like to focus on specific disease based programmes covering fields such as Dengue Fever, Trachoma or the three diseases identified in this year’s WHO report as representing the greatest risk for global health emergency.

Another step might be to call for a more fundamental review of the social contract with global pharmaceutical companies (the TRIPS agreement), to ensure that the risk and rewards of investment in research and development (by universities and pharma companies) are adequately incentivised for contribution to global health priorities. This could include reassessment of the way in which the research and development of medicines is funded and priced in high and low income markets.

It is perhaps too easy to blame pharmaceutical companies for neglecting certain diseases and issues concerning drug delivery in low income countries It might be more constructive to evaluate their performance in supporting access to medicines. The Access to Medicines Index, which is supported by UKAID, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs reviews the performance of 20 of the world’s largest research-based pharmaceutical companies on how they make medicines, vaccines and diagnostics more accessible in low and middle-income countries. It highlights best and innovative practices, and areas where progress has been made and where action is still required. It has been published every two years since 2008. You may wish to view the index here. This provides a clearer way to target those companies who need to improve their performance, to call for the adoption of best practice and perhaps to celebrate those that act as responsible global corporate citizens. Medsin members could play a role in focussing student attention on those pharmaceutical companies that need to be encouraged to increase their efforts to support global health equity.

Stop Press

Since posting the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness (CEPI) have announced a $460 million programme to develop potential vaccines for the high priority NTDs noted above. .

Noncommunicable Diseases and Global Health Equity What Can Medsin Do?

Noncommunicable Diseases (NCDs) attributable to factors such as: poor diet, smoking, alcohol and other drug consumption are the leading causes of death (~70%) and poor health (~60%) globally. To address their impact, action is required to improve the regulation of global corporations that promote unhealthy products and lifestyles, to reduce illegal trade in drugs, cigarettes and alcohol and to increase awareness and community action to protect our health. This calls for both strengthened global governance and whole society action for health.

Medsin is engaged in this movement through IFMSA, which is a participant in the WHO Global Dialogue on the role of non-State actors in supporting Member States in their national efforts to tackle noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A report of their meeting in October 2016 can be viewed here. In this note I have attempted to suggest what Medsin might contribute to efforts to address this global health and equity challenge.

The statement by the co-chairs of the WHO Global Dialogue on NCDs called for NGOs to redouble their efforts to advocate for action at global, national and local levels, but their conclusion on progress to date was frankly depressing:

“Nearly three-quarters of all countries showed very poor or no progress in 2015 towards achieving the implementation of their time-bound commitment to address NCDs made at the United Nations General Assembly in 2011 and 2014. The current rate of decline in premature deaths from NCDs is insufficient to meet target 3.4 of the Sustainable Development Goals to, by 2030, reduce by one third premature mortality from NCDs. This poses a particular challenge to low- and middle-income countries, where premature deaths strike hardest, and among populations already made vulnerable due to lack of equitable economic, social, and environmental development trends”.

To understand the causes and consequences of NCDs in total or for individual diseases, globally, for individual countries and even regions of the UK, the best source is the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation, Results page here. The Global Burden of Disease Tool, Data Visualisations, Country Profiles and research reports are all very useful. They show expert estimates of the impact of the main behavioural and environmental risk factors associated with diseases and their outcomes, in terms of Deaths, Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYS), Years of Life Lost due to premature Deaths (YLL) and Years Lived with Disability, weighted for disability (YLD), note that DALYs=YLL+YLD.

I used these data to develop tools for evaluating the value for money of behaviour change interventions, in terms of health and social cost savings, for smoking cessation, alcohol harm reduction, improved diet and activity, breast feeding continuation and bowel cancer screening response available here. These tools, which were funded by the DH, are intended to encourage local authorities to value behaviour change and strengthen programmes to reduce NCDs, of necessity they are rather complex and require evidence or consensus on the degree to which any change in behaviour persists. As Mark Twain famously said “Giving up smoking is the easiest thing in the world. I know because I've done it thousands of times.”

In practice studies show that persistence in behaviour change is greatly enhanced by community support. Medsin can influence fellow students to reduce their risk of NCDs by encouraging and supporting behaviour changes such as: healthy eating, quitting smoking, activity improvement and responsible drinking and drug use. Moreover, advocacy for action on NCDs and support for behaviour change can help raise awareness and promote a whole society response. Such measures might include: global regulation of food to reveal their sugar and salt content, regional support for the food labelling “traffic light system” promotion of the UK “Be-Food- Smart” app and local action to encourage supermarkets to offer healthy food isles.

This is another example of “Global Health, a Local Issue”, in which global and national advocacy can influence communal attitudes and personal choices.

Migration of Health Professionals and Global Health Equity

In December 2016 the UN Secretary General (then Ban-Ki-moon) responded to the WHO “Report of the High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth”. He noted the Commissions finding that “Changing populations will generate a demand for 40 million new health worker jobs by 2030. However, most of these jobs will be created in wealthier countries. Without action, there will be a global shortfall of 18 million health workers to achieve and sustain universal health coverage, primarily in low- and lower-middle-income countries”. The report “Working for Health and Growth: Investing in the Health Workforce” here has important implications for Medsin members and health equity.

The conclusion of the report is that investment in health staff training and development is good for economic and social development and is essential to the Sustainable Development Goals. Ten recommendations are proposed on what needs to be changed in health employment, health education and health service delivery to maximize future returns on investment and how to enable the necessary changes:

1. Investment to create good health sector jobs, particularly for women and youth.

2. Recognise and strengthen womens’ roles in all areas of health delivery and leadership.

3. Scale up high quality education and lifelong learning for health workers.

4. Reform health systems to focus on high quality, affordable, integrated community care.

5. Harness the power of ICT to enhance health education and delivery.

6. Invest in IHR capacity, develop resources for humanitarian aid.

7. Raise finance from domestic and international aid sources necessary for this investment.

8. Promote international and national intersectoral cooperation and engage civil society.

9. International recognition of qualifications, reduce negative impacts of migration.

10. Research into health labour markets and monitor them using common measures.

My experience of helping 5 Universities in East Africa to develop a common curricula for a Masters Degree in Advanced Nursing Practice and Leadership, and a review of the Kenyatta Teaching Hospital and reviews of other hospitals such as the Kantha Bopha in Cambodia supports some of these conclusions. I certainly agree that in many low-income countries the problem of retaining health professionals is compounded by a lack of adequate health sector employment and advancement opportunities outside the major towns. Health services are often led by women nurses, particularly in rural areas, their role needs greater support and recognition through training and pay. While some health workers benefit from advanced courses in universities, continuing education using IT and blended learning, of a high standard and leading to recognised qualifications is likely to be more affordable for most. Short courses offered by many aid projects often fail to meet these standards.

Hospital care often dominates the budget of low-income country health systems and this is too often confined to large towns with poor links to community care. ICT could transform the delivery of health services, but only if used as an element of an integrated transformation of health worker training and integrated community health service delivery. It is not clear to me that the model offered by health professional bodies based in high income countries is most relevant to low income countries, where doctors are unlikely to be based outside major towns where they can access private patients. The potential of ICT to transform healthcare in low-income settings could be constrained by traditional professional roles and education. There have been various models of integrated community based healthcare, I find the Health Extension Package approach developed in Ethiopia by my friend Tedros Ghebreyesus most relevant see here.

The USA and UK are the two most significant targets for health worker migration. In recent years the NHS has recruited up to 3,000 doctors and 6,000 nurses per year trained in other countries. Most are from low-income countries where health worker shortages limit the provision of services and hamper human development. While some return to their country of origin with enhanced skills and experience, most do not. This problem has been recognised and various International Agreements and Memoranda of Understanding have been established to try to ensure responsible recruitment. But in practice it is not easy to limit recruitment, workers have the right to use their skills wherever they choose and if they are not recruited directly to the UK they may move to another country and displace workers who then migrate to UK. A simple answer to this problem would be an international agreement for the recipient country to repay the cost of training. This should not be a direct employment cost but a parallel payment that would both enable the provider country to train more workers and encourage the recipient country to increase its health education budget. Medsin members may be justified in calling for the UK to “Pay its Way” in health education as a contribution to global health equity.

Can Medsin Make Global Corporate Social Responsibility Stick?

This week (Jan 18 2017) the World Economic Forum has spent considerable time discussing its call, first set out in a 2012 paper for "a new social contract based on a new economic model, which places equal emphasis on growth, employment and social protection”. No doubt many of the bankers and global corporate leaders, who flew into Davos in their private jets to discuss world poverty and sustainability, will sign up to demonstrate their commitment to global corporate social responsibility (GCSR). They may have even agreed with Theresa May’s warning that globalisation could stall unless it was made to work for everyone. Though some bankers seem encouraged by Trump’s version of free trade, as set out in his inauguration speech, that puts America first and last. The WEF’s Inclusive Growth and Development Report 2017 available here points to growing income disparity within both rich and poor countries. It suggests measures of the impact of globalisation on equity and even questions whether the current model of global capitalism can survive. But do global corporations’ hand wringing and expressions of social responsibility have any reality or are they just a new version of “greenwash”? Can Medsin make global corporate social responsibility for health a reality?

Corporate social responsibility has long been a favoured page on corporate web sites, usually focused on commitment to environmental standards and seldom mentioning global health. In 1999 Kofi Annan introduced the UN Global Compact, which encouraged some 9,250 companies to sign up to a set of values, which are now linked to the Sustainable Development Goals. This also provides a framework by which adherence to the global compact may be assessed, but it is unclear who should apply this.

Another way of looking at GCSR is that it relies on voluntary commitments, to values and codes of conduct, avoiding any form of global governance of business by the UN. The current process for agreeing trade tariffs and regulations resulted from US objections to the proposal for a UN International Trade Organisation. The General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) was established in 1948 and reformulated as the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 1995. It is not a UN organization but a forum for international agreements between governments. It has been open to discussions with NGOs on Corporate Social Responsibility issues but does not monitor or regulate such matters.

Is GCSR a step in the right direction? At first glance it seems only positive that corporate leaders should address economic inequity and other social impacts of globalisation, but this cannot replace global governance and regulation. It seems perverse that global companies should be the bodies that choose how they should be judged and to select whether or not they will accept regulation. At present global companies are free to setup complex structures and internal pricing mechanisms so that for example the value generated by mining operations in Zambia are taxed at a favourable rate in tax havens see here.

While some companies may choose to provide healthcare for their workforce in South East Asia, others avoid such costs and outsource their production to low cost sweat shops operating in unsafe conditions (a sweatshop is defined as an establishment breaking two or more labour laws). One possible way forward is for civil society groups to come together to raise awareness amongst customers of the global corporations, to promote the value of ethically produced goods and denounce those that fail to meet acceptable standards. This has been effective in changing the behaviour of some producers such as Nike see here. But many global companies do not produce consumer goods and are difficult to pin down. So perhaps it may be necessary to face down these companies where their goods are produced see the training course on leading responses to globalisation here .

Even if such measures can be made effective it is important to stress that self-regulation is not a substitute for the governance required for this new era of globalisation see the article by Arnel Karnani here.

Stop Press

Since posting this I discovered that a good friend of mine and the wisest man I know Randall Peterson was invited to speak at Davos, his views on responsive and responsible leadership and Trump are worth listening to here.

27 Jan 2017

Is this the Beginning of the End of Antibiotics?

September 2016 saw the death in Reno of a woman in her 70s whose condition proved to be resistant to all 26 antibiotics available in US hospitals. She developed a rare infection after treatment in an Indian hospital for a broken femur and was hospitalised with sepsis after returning to Nevada. The news, which was released in January this year, has raised fears that the era of total antibiotic resistance has begun.

This could fundamentally affect the future of medicine, threatening the lives of hundreds of millions of patients across the globe. Experts have warned of the danger of rising antibiotic resistance for several years, due to their misuse in human medicine and animal husbandry and the lack of controlled distribution in many countries. In seeking to understand this issue I found I was able to purchase a single dose of a fourth-generation antibiotic in a wayside shack near Phnom Penh. Medsin members will understand that this is a recipe for developing antibiotic/antimicrobial resistance. While there are a limited number of new antibiotics being researched, it is claimed that the economics of drug development no longer work. New antibiotics are increasingly expensive to develop and require many years of clinical trial, at the same time the speed at which antibiotic resistance develops and spreads across the globe, to make them useless, has increased alarmingly.

In 2016 the UK government published a review with the support of the Wellcome Trust entitled “Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance”. In introducing the review David Cameron underlined the gravity of this issue: “If we fail to act, we are looking at an almost unthinkable scenario where antibiotics no longer work and we are cast back into the dark ages of medicine". The report, which is available here , put forward ten recommendations, estimated to cost $40 billion over ten years:

- A massive global public awareness campaign

- Improve hygiene and prevent the spread of infection

- Reduce unnecessary use of antimicrobials in agriculture and their dissemination into the environment

- Improve global surveillance of drug resistance and antimicrobial consumption in humans and animals

- Promote new, rapid diagnostics to cut unnecessary use of antibiotics

- Promote development and use of vaccines and alternatives

- Improve the numbers, pay and recognition of people working in infectious disease

- Establish a Global Innovation Fund for early-stage and non-commercial research

- Better incentives to promote investment for new drugs and improving existing ones

- Build a global coalition for real action – via the G20 and the UN

This is an issue that affects global health across all national boundaries and it is also an intergenerational issue, as antimicrobial resistance will have greatest impact on Medsin members’ millennial generation and beyond. It also raises issues of global health equity, because as effective antimicrobials become rarer, there is little doubt who will be last in line for them. Medsin members may wish to consider their position on this question. It seems that the problem is clear and there are well researched economic, social and medical answers available. What is not evident is action to implement these solutions. Medsin may wish to consider how to stimulate decisive action on this issue.

Stop Press

On February 3rd UCL researcher Dr Ndieyira announced his team at UCL had developed models of how antibiotics interact with cells "Our findings will help us not only to design new antibiotics but also to modify existing ones to overcome resistance." See the UCL Antimicrobial Resistance Network here

How Should We Respond to the Trump Travel Ban?

The recent Executive Orders signed by Trump, put in place a 90-day block on entry to the US for citizens from Iran, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, Libya and Somalia. It suspends the admittance of all refugees to the US for a period of 120 days, and terminates indefinitely all refugee admissions from Syria. It also caps the total number of refugees entering the US in 2017 to 50,000 – less than half the previous year’s figure of 117,000. Aspects of the ban have been challenged in a US court and Obama and the US Acting Attorney General, Sally Yates, (who has since been fired by Trump), have stated that they find the ban discriminatory and counter to the US Constitution. Across the US and the world there have been protests against this action as racially and religiously biased, without any foundation in evidence (of claims that terrorists posing a threat to the US are amongst these migrants). Moreover the ban is counter-productive, since Islamic extremists seek to divide and isolate Moslem from Kāfir, in the hope of recruiting more of the 3.3 million American Moslems to their cause and Trump’s actions will clearly assist this aim.

While a petition to ban Trump from the UK has more than 1.5 million signatures, it is important to recognise that Trump’s perverse views are supported by the majority of the Republican Party and perhaps the American electorate. Protests against this action must therefore also be matched by steps to engage and inform the American electorate, or at least not to conform to a stereotype of anti-American, flag-burning mobs. Some protestors have realized this and have focused on the fact that the bans are “Unamerican”, “Unevidenced”, “Counterproductive” and will harm US interests and popularity (soft power). Protests have largely been calm and dignified and have conveyed a positive message of welcome for migrants to this country.

A programme to empower new migrant women to integrate as representatives of their community in Portsmouth here taught me how sensitive, migrant families are to signals of racism or welcome. For example, they told me that when they saw anti-migrant headlines in the Daily Mail they felt frightened to walk down the street. On the other hand they described the opportunities provided by the programme to improve their English, learn about their rights, health, employment and education opportunities and to take up roles as Community Advisers, as transformational for them and their families. It is time to step up action in this country to address prejudice as it seeps across our borders, unchallenged by our political leaders and to improve opportunities for integration.

From a global health equity perspective the threat posed by Trump’s ban arises from the culture of racist, anti- Moslem bullying and violence it promotes. As already noted depression and suicide, often fueled by prejudice and bullying are major health issues for adolescents and this is also true for young adults up to the age of 30. To this must be added the impact of interpersonal violence. In the UK we saw that anti-migrant sentiment licensed by Brexit discussions resulted in an increase in racist attacks. The consequences of such attacks in a country where gun ownership is uncontrolled is frightening. In the USA about 1/3 of homes contain a gun, more than 33,000 people die each year as a result, more than 13,000 homicides and more than 20,000 suicides and accidents.

Stop Press

Since posting there have been protests across USA and the world, disputing the ban and expressing support for migrants. This has included participating in World Hijab Day, on 1 February by posting pictures online of people of all faiths and none wearing the headscarf. Thousands of lawyers have taken action to challenge these Executive Orders, local judges have taken action to mitigate the effect of the bans by, for example, rescinding application to Green card holders and giving exemptions to travellers held at airports. A Federal Judge then temporarily deferred the application of the ban to all migrants on the basis that it is unconstitutional.

17 January 2017

What will a Trump Presidency Mean for Global Health Equity?

Trump’s inauguration is an important moment for Medsin Members to consider what this presidency and Republican domination of the senate, congress and soon, the supreme court, may mean for global health equity. How might aid, trade and global governance of issues such as: human rights to health and protection from climate change be affected? In this brief note I suggest some starting points for thinking through these questions and monitoring the threats to global health equity they represent.

The USA is the largest source of international aid, it provided $32 billion of the $132 billion total Official Development Assistance (ODA) in 2015, though this is one of the lower contributions as a percentage of Gross National Income (0.17% of GNI). It is also a major source of private and voluntary sector aid. This may be compared to the UN commitment made in 1970 to achieve aid flows of 1% of GNI (0.7% from ODA and 0.3% from other sources). The UK is one of only 7 countries that meet this commitment to ODA. Trump and his team have offered few clues as to their attitude to aid, though he is on record as saying that “We should stop sending aid to countries that hate us”. During the last Bush presidency, US aid was increased from 0.11% to 0.21% of GNI (from 2001-2009), it has since declined to 0.17 % of GNI but Trump shows no sign of willingness to increase it. A central element of the Bush administration health aid was the President’s Emergency Plan for Aids Relief (PEPFAR). This programme has been criticised for placing too much emphasis on favoured countries and religious partners. Its “ABC” approach, emphasised, unproven “abstinence” and “be faithful” programmes with less emphasis on “use a condom” and no support for needle exchange programmes. US aid was also withheld from agencies offering guidance on abortion (the so called "Gag Rule"). These reflect Republican values and are trends that may be reintroduced by the current regime. Ted Cruz has already called for the suspension of US contributions to the UN (including the WHO) in response to a Security Council vote on Israel.

Trump policy on trade is clearer, with commitments to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, (TPP), which has not yet been agreed, renegotiate the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and no doubt he would have withdrawn from the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), had it not already been dead in the water. Advocates for global health equity have also challenged these deals because they give too much power to global corporations, encouraging a “race to the bottom” for health and safety regulation. Trump’s opposition to globalisation is based on protectionism, presented as protection for US workers against low paid overseas workers but also protecting US global corporations from regulation in the interests of fair trade to promote global health and equity. This may result in global corporations (27% of which are based in USA) being given even more power to bully low income countries, with the backing of US political power. Watch out for backtracking on unresolved issues around health and TRIPS (Trade Related aspects of Intellectual Property Rights). Currently this World Trade Organization agreement that protects patents is mitigated to some extent by the 2001 Doha declaration which asserted that TRIPS should not prevent states from dealing with public health crises, such as HIV/AIDS. But since Doha the USA and some other pharmaceutical producer nations have been working to minimize its effect.

An indication of the Trump and Republican attitude to human rights to health can be seen in their opposition to “ObamaCare” (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act) with plans already in place to defund, limit and replace it with some version of Health Savings Accounts. The question for health equity advocates is whether the denial of access to healthcare as a human right for some 20 million Americans is likely to influence attitudes to global health. More specifically the Republican focus on defunding women’s health and rights to health choices, services for the LGBT community and family planning are danger signs for global health equity.

Trump has tweeted “The concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive.” Whether, in this post truth world, this is intended to be taken literally or not is unclear, but Trump has said it is not worth spending money on climate change and that he intends to withdraw from the Paris Climate Change Agreement. All those who are concerned at the threat climate change poses for global health equity and the lives of future generations and believe the overwhelming consensus of scientists and common sense observers will be horrified by this. Moreover, withdrawal from the Paris Agreement threatens the basis of global governance. How can a nation retract a carefully negotiated agreement at the whim of its ruler?

The challenge for Medsin is not simply to oppose Trump, it must be accepted that he is the elected leader of the world’s most powerful and influential country. It is therefore important to consider how the damage of his policies can be averted or mitigated and what role Medsin action can play. Trump does not enjoy the support of all Republicans, many have more balanced views, indeed he himself may be more sane than he appears. “You campaign in poetry. You govern in prose” or in his case perhaps “You campaign in tweets. You govern in mashups”. A lesson to be learnt is that Medsin must stress that global health is a local issue that affects everyone. It is as important for the families of America as it is for academics and experts. At the same time advocacy in this country, Europe or at global fora must address the new reality (show) presented by Trump. During the last Republican presidency swift action was required to offset the withdrawal of USAID funding from family planning services that provided information on termination services. It now appears that global action will be required to mitigate the impact of many potential Trump policies.

Stop Press

Since posting this Trump has announced his personal support for torture, signed an order for the reinstatement of the Gag Rule, withdrawn from trade negotiations, and announced his intention to role back environmental controls. In the same month the American Public Health Association have declared 2017 the "Year of Climate Change" with the intention of raising awareness and action, best of luck with that!